|

Re: Why no Packard in a "Packard"?

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Home away from home

|

Hi

Hope some of these facts presented from two good sources will shed light on the whole Connor Avenue move. Excerpted from "Connor, Briggs and Chrysler: Trend and Fate" by John M. Lauter, The Cormorant, Spring 2007, Number 126, pages 2-11. "...the Connor plant was itself World War II surplus. Built for Briggs in 1940 for airplane component manufacturing and quickly enlarged a year later, it became an ideal sized and located facility to move Briggs' Packard work to after the war." "Shortly after the war, Briggs moved all Packard production to the 759,749-square foot Connor Avenue plant." "Walter O. Briggs died on January 17,1952 in Miami. In the face of daunting inheritance taxes his heirs decided to sell the automobile body business. Chrysler, their largest customer, was the logical choice".........."The sale closed on December 29, 1953. For $35 million, Chrysler gained all equipment, tooling and 12 plants - 10 in the Detroit area, one in Youngstown, Ohio and another in Evansville, Indiana, and added 30,000 Briggs employees to their payroll. The Briggs purchase found all body-making facets of Chrysler reorganized as 'Chrysler ABD" (Automotive Body Division)." "In a press release dated December 29, 1953 (the day the sale closed), Chrysler stated, "Automotive customers of Briggs, including the Packard Motor Car Company for bodies and the Hudson Motor Car Company for trim materials, will be served by the Automotive Body Division, under Chrysler management." Chrysler obviously thought better of this aspect of the business after acquiring Briggs, notifying Packard that they would no longer provide bodies to Packard after the 1954 run. James J. Nance was known to be on friendly terms with Chrysler president L.L. 'Tex' Colbert; perhaps Packard would have suffered a more curt disruption of their body supply if these two men were not social with each other." "The move was sold to the shareholders and the media as 'modernization', getting all assembly operations on one level, but it was really a case of 'bringing the mountain to Muhammad." Packard's body assembly operations were there, in place, and operating. It was probably easier for Chrysler to lease the facility to Packard than deal with disposition of the equipment and property immediately after the Briggs acquisition. We know that the Connor plant never functioned well as an automotive assembly factory and that the production supervision and staff at Packard pulled off a miracle transferring operations from the 3,000,000-plus-square feet of East Grand Boulevard space to the meager 759,749 square feet (a figure that Packard staffers contested once in the plant) at Connor." "The end came in the summer of 1956, when all Detroit (Packard) operations were ended by Curtiss-Wright. Studebaker-Packard held the lease on the Connor plant until June 11, 1957, after which it reverted to Chrysler. According to documents in the Chrysler archive, the plant was 'in such poor condition a supplemental agreement was made to demolish it on December 30, 1958." The demolition was completed by August 8, 1959. At 19 years of age the Connor plant must have been an albatross to Chrysler, too small for any significant production and too big for sub-assembly work. As for the statement concerning its poor condition, it is hard imagine that Packard caused such a degradation of the facility in three short years. Perhaps Briggs was lax in maintenance." Photographs show 1954 Packard bodies were only painted in their finished colors but without any interiors, chrome trim or glass before shipment to Packard. Excerpted from The Packard 1942-1962 by Nathaniel T. Dawes, page 123: "In May (1954) the company negotiated a five year lease with Chrysler, at an annual cost of $0.8 million with option to buy. Nance immediately had Ray Powers, vice-president of Engineering, who had done the Utica plant begin layout of a final assembly facility." Author notes he was assisted by Neill S. Brown and John D. Gordon. "These three (Powers, Brown and Gordon) had until September 16, 1954, to finalize the plans and organize the logistics to implement the plans. That date is when the last 1954 Packard body shell came off the line. Starting September 17 it was to be an organized race against time to complete the renovations and begin assembly of the 1955 models." "The Connor Avenue plant went from shutdown on September 16, through a complete renovation, began production, and the first 1955 Packard drove out the door on November 17, 1954. That is exactly 62 days, from shutdown to production of the first automobile on the new line." So, for $800,000 annually, Packard leased a facility with a fraction of the floor space (759,749 sq.ft. vs. 3,000,000-plus sq. ft.) it had utilized at East Grand Boulevard now to do complete car assembly which still included the body assembly. How much was expended to tear up everything in place at both plants and reinstall it all in inadequate square footage in a compression time frame isn't noted. All this on top of a radically changed product line far more complicated and unfamiliar to the assembly staff working in a new unfamiliar facility. The learning curve must have been steep indeed. If Packard had been a choice job in the auto assembly industry beforehand, it must have turned into a nightmare for many long-timers. While it cost significantly to make this move, funds better utilized otherwise, blaming the complete $29 million loss for 1955 on the plant move directly is incorrect. What the action did was set in motion a hailstorm of market troubles of late introduction, badly delayed dealer deliveries and myriad quality problems that consumed months and considerable resources to rectify, worst of which was damage to their public reputation for quality and reliability. The 1955 loss was the indirect result of a whole sequence of unfortunate events, incorrect assumptions and bad decisions. No small share of loss was also extracted by the taking on the Studebaker operating expenses which the combined corporation was obliged to do. Steve Addendum: To my description of the two photos showing painted bodies without trim or glass, examining the photo on page 3, two transport trailers loaded with bodies show them to have glass and chrome trim in place. Apparently they were returned to an assembly line when specific orders were scheduled.

Posted on: 2012/4/19 8:43

|

|||

|

||||

|

Re: Speedster & Garage

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Home away from home

|

Hi

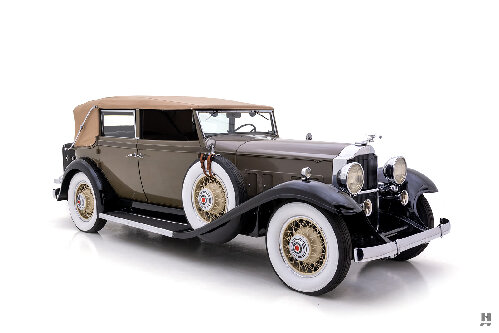

Absolutely wonderful lines and proportions! Derham built that design under license from Hibbard and Darrin who created it as their Torpedo Transformable four door convertible/phaeton with the top material flap between the side windows and second cowl windshield. The convertible coupe version has the same low top, elegantly angled windshield and door frame with a low deck. In addition to Packard, they were mounted on Cadillac, Chrysler Imperial, Stutz, Hispano-Suiza and Rolls-Royce chassis, in either configuration. There is a particularly gorgeous example extant on the '30 745 Deluxe Eight.....just stunning! Steve

Posted on: 2012/4/15 7:30

|

|||

|

||||

|

Re: Is It Me Or the Car?

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Home away from home

|

Hi

Of the Muscle car and Street Rod cliches I've observed, to paraphrase Auntie Mame "Automotive History is a banquet, and those poor blighters are starving to death!" Their myopic outlook deprives them of a world of interesting and worthwhile cars that don't qualify as "cool" by their definition. No matter, their attitude contains the seeds of its own punishment. Enjoy your Clipper, you'll find more who do than don't or worse, won't allow themselves to. Steve

Posted on: 2012/4/9 12:15

|

|||

|

||||

|

Re: We haven't had a good "What If?" for a while, so.....

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Home away from home

|

Hi

Thanks gentlemen, hope this was thought-provoking, generated consideration of how events might have turned out differently. Patgreen: The following is the definition of 3-box styling from the Glossary of A Century of Automotive Style: 100 Years of American Car Design by Michael Lamm and Dave Holls, page 298: "Box, one-, two-, three-: Body morphology is often described in terms of one-box, two-box and three-box. A one-box body usually refers to a van, whose body looks like one big box. A station wagon or something like the VW Rabbit qualities as a two-box body, the hood being one box and the cabin the second. And a three-box body is usually a conventional sedan or coupe: hood, cabin, trunk. Also called "one-, two-, and three shape."" Personally, I think of the three boxes defined by box one as everything ahead of the windshield, box two as everything behind the windshield and below the window beltline including the integrated trunk, and box three as everything behind the windshield and above the window beltline. The accepted definition probably works just as well for most. In the case of the touring sedan, with an appended trunk, it could be considered a three box by the accepted definition, though strikes me more as a two and a half box design. The 60 Special's integrated trunk with the passenger cabin body mass seems more the second box, crowned by a separate three box. Choose whichever definition that works for you. The five passenger victoria or club coupe is a three box configuration. Bill Mitchell's genius was lengthening the passenger compartment of a club coupe, adding two more doors but keeping the roof 'box' separate. Or maybe it was taking the close-coupled club sedan and integrating a coupe trunk.....either way, he jelled the sedan body configuration we still have today. Pretty smart for a 25 year old guy! Small wonder he became Harley Earl's successor and gave us some marvelous styled '60's cars such as the '63 Corvette Sting Ray, '63 Buick Riviera, '66 Oldsmobile Toronado and '67 Cadillac Eldorado. The entire 1965 GM line-up is the first model year he had completely overseen restyling every car line, very nice job by my estimation. Ross: Packard buried themselves in tooling cost for years, frequently for minimal volume. With regard to 1937, the Senior models were still composite body construction, wood frame, metal panels. Variety was less costly in terms of large, expensive dies. For 1938, the new all-steel Junior bodies, shortly to be shared with Seniors, included stamped, one-piece roof shells which were considerably more costly to tool. The all-steel 'turret' top was the industry norm, a feature they couldn't fail to offer. Main of the reason for the Clipper's limited body style selection had to do with the panicked nature of it's development and late introduction. Time was too scant for them to develop and tool the their usual wide selection of bodies. The Clipper roof shell stamping, the largest in the industry at the time, was one of the motivations for them to turn their body construction work over to Briggs. Briggs perhaps gave them a unit price less than they could so in-house but it set up a precarious situation being dependent upon just one source for a major component. By 1941, there were also the demands of war materiel production which was tying up die-shop resources throughout the industry. There was also something of a voluntary curtailing of civilian work in preference to war material needs even before Pearl Harbor. After the war, with every carmaker scrambling to get die work done for their newly restyled postwar, Briggs really had Packard over a barrel when it came to updating the Clipper for the 22nd Series. Packard had collaborated closely with Brigg's in-house styling department to develop the new styling during the war. To re-equip and tool up for body construction at East Grand was by then prohibitably costly: For them to suddenly seek bids from Murray or Budd would have been going way out on a limb, especially since both were up to their arms in tooling work. In the book mentioned above (recommended reading for a greater understanding of not only Packard but the industry and the era in general), the following section confirms the massive cost, from page 227: "George Christopher was ecstatic, because an all-new body would have been much more expensive. And yet the 1948 Packard, even though it kept all the Clipper's underbody, inner sheet metal, roof and decklid, was anything but a retooling bargain. According to Packard Historian William S. Snyder, who researched company record, Packard spent nearly twice as much tooling its 1948 models as Hudson did that same year on a truly new body. "Maybe Packard had become too accustomed to government work," said Snyder." Other factors that drove up the cost of everything after the war were the shortages of workers and basic materials, steel was at a premium for years. War materiel production had been done with cost-plus government contracts including wages which were much more by the end of the fighting. No one was going to reset wages to pre-war levels. Consider the escalation of the base price of the basic Chevrolet four door sedan: 1941 at $795, by 1946 at $1,123, by 1948 at $1,371. So, though I don't have specific industry figures to offer, Packard wasn't alone in grappling with increasing tooling and production costs in the postwar period. Jim L. in OR: By the mid-'50's GM's design staff came to perceive that Harley Earl was losing his 'touch' and "groping" for a styling direction for the late '50's. As you note, many of the resulting cars were heavy-handed and less-appealing unless over-decorated is one's taste. Earl was due to retire November 30, 1958 at 65 years old. After thirty years of starting, then developing GM Styling into the major industry force that it became, who could blame the fellow for wearing out. As far as the overwrought styling that characterized that era, Earl himself was the main driver behind that idiom, so maybe it became too much even for him. But Earl had mentored Mitchell, who had already demonstrated his ability for clean, tailored design, into the prefect successor, so his legacy was assured. Mitchell drove that trend toward cleaner styling that came throughout in the '60's. Steve

Posted on: 2012/4/9 11:57

|

|||

|

||||

|

Re: Why no Packard in a "Packard"?

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Home away from home

|

Hi

While there were service engines available, management would be reluctant to commit them to a further production series with no back up production taking place without major expense. The additional problem would be what to do about the transmission since Ultramatic production ended at the same time as the engine. The engineering work to adapt the Packard engine to the Studebaker Flightomatic and whether it was up to the challenge of that powerplant was just one more hurdle to clear for such a mate-up. Mostly it comes down to a company in dire financial straits utilizing what minimal resources they had in hand to try to bridge one of the most difficult periods of their existance. Survival for the corporation was their focus and that met concentrating on the volume sales. As much as we like the special models, the bread and butter cars allowed a car company to survive. In '57 and '58 S-P wasn't completely sure if it could come up with bread and butter cars that would sell enough volume to allow survival. Churchill hit upon the Scotsman concept and it turned out to be nearly their bestseller. They are about the plainest jane cars one can imagine but the market responded and helped them bridge to the Lark era. Initially the Lark sold well and generated $28 million in profit for '59, less in '60. Of course, as soon as the Big Three introduced their compacts, all but Rambler and VW were forgotten about. Any thoughts about continuing Packard or a revival thereof would have had to wait until the corporation itself were back on solid financial ground again. Steve

Posted on: 2012/4/8 11:59

|

|||

|

||||

|

Re: 1952 Patrician - Derham or Henney?

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Home away from home

|

Hi

The plot thickens! Glad those Ebay photos turned up, I went looking for the disk I had saved them on, but no luck. Thanks for posting them. Typically, Derham mounted their coachbuilder script at the front fender edge, just above the trim. While they appear to be missing, one wonders if a couple of telltale mounting holes might be there? I sure hope such a worthwhile coachbuilt Packard has been saved, love to see it restored. Steve

Posted on: 2012/4/8 11:36

|

|||

|

||||

|

Re: We haven't had a good "What If?" for a while, so.....

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Home away from home

|

Hi

Always enjoy a thought-provoking What If! So many good points made so far, but I'll have take up the original question first. Earl would have viewed a stint at Packard as a stepping stone to the premiere position in the field as leader of GM's Art and Color, anything less would have been intolerable. His talent and design sense was mated to an immense ego, one that could never be happy affecting the design direction of a relatively small, independent carmaker. Earl knew mass production was where he could have the greatest affect, as market saturation had a way of creating taste for his design idiom. He learned quickly with his '27 LaSalle that high style could influence the whole industry to copy his direction. ".......HH56 makes a sobering argument about the critical role of mgmt. Over at GM it really wasn't Earl by himself, it was him and Sloan and others acting in concert." Where Earl and the Packard management would have quickly run afoul was Earl's willingness to try bold new styling that owed nothing to the current idiom, as exampled by the '34 LaSalle. Cutting his design teeth in California, he understood a percentage of the upscale tastemakers would embrace progressive styling as an indication of their social outlook. His success in the pre-GM period was presenting styling counter to the prevailing staid, conservative norm. More importantly, Earl understood the major role styling would come to play in influencing buying decisions as the mechanical aspects became more robust and dependable for all price segments. The other adherent of this outlook was Alfred Sloan, who supported Earl's judgment, abetted his drive to develop GM Art & Color into the styling juggernaut it became. Sloan also had the final say when engineering might bridle at some design or feature deemed too costly to produce. His trust in and support for Earl's judgment was without question and absolutely indispensable . By contrast, Macauley and board were pleased enough to allow son Ed and his small group to develop evolutionary designs, always with the final approval by the engineering department. This approach left Packard woefully ill-equipped to respond as GM drove customer preference by sheer saturation. It also put them in a more vulnerable position once they entered volume competition with GM through the Junior series. Had they taken note of Chrysler and the other independent carmakers and their design department developments, they might have realized how far behind they were falling. Packard's evolutionary approach was fine for the luxury car segment in the 1920's on into the mid-1930's, until the introduction of three seminal cars which appeared on the heels of the '34 LaSalle. One was the '36 Cadillac 60 which began the democratization of the luxury car in earnest below the $2,000 segment. Less a matter of style, it proved the acceptance of a smaller, owner-driven, high-performance luxury sedan, the "pocket luxury car" if you will. The cultural outlook was changing to a more egalitarian one that prized less the display of wealth through the grandiose luxury cars offered up to that time. Concurrently, the Cord 810 demonstrated how lowered, avant-garde design could grasp the attention of upscale customers out of proportion to actual sales numbers. To bring about the third influential car, fortuitously Earl had hired 25 year old Bill Mitchell to head Cadillac styling in late 1935. His first assignment was to design a youthful new LaSalle sport sedan. Also fortuitously, management decided to build it as a Cadillac, realizing the role of styling leader should be held by their flagship, not by it's companion marque. The stage was now set. "......based on the hard historical fact that the 60 Special changed the industry fundamentally, particularly the luxury car segment. In one sweep of Bill Mitchell's brush the traditional touring sedan was done. " Key to the success of the 60 Special was it's breakthrough presentation of the 3-box sedan configuration, instantly rendering the touring sedan as old-fashioned. While the latter still had market life left in the lower priced segments, upper medium and luxury customers enthusiastically embraced this exciting new sedan architecture. Heretofore, the 3-box sedan had been seen on occasional custom bodies as an extension of the club sedan. Suddenly, the '38 60 Special made available to tastemakers the ideal combination of capable chassis, owner-driven size, lowered 3-box configuration in a production sedan of moderate luxury car price. Bingo! Earl and Sloan realized instantly they had a winner when it quickly accounted for 40% of Cadillac sales. Never one to let a success go unexploited, Earl set Art & Color upon the task of creating sportier mass-market 3-box sedan concepts. The introduction was reserved for the upper series models of each make, Pontiac through Cadillac; whereupon the C-body torpedo sedans and coupes took the 1940 market by storm. To understand the long-term major sea change taking place initiated by this new configuration, touring sedans dominated in 1938; by 1949, the 3-box sedan supremacy was complete. This is the point were Packard was running scared to death of GM, realizing it's volume 110 and 120, so central to profitability, were going head to head against these popular new styles while still fielding reworked '38 model touring sedan bodies. The panicked initiation of the Clipper project began at this point. Indicative of the complacent attitude settling over East Grand mahogany row is the very fact they had failed to act on this important design trend a year or two prior or better yet, initiate it. While it's true Packard's market thrust had turned largely to the medium-priced segment where the touring sedan still held sway, their own 'pocket luxury' '39 Super Eight offered nothing to attract the important tastemaker market. It was the "lugs loosening badly and wheels wobbling" for Packard's market position. The Clipper arrived almost in the nick of time, at least it kept them in the game for a while. Frightening to consider if it hadn't and they had to enter the postwar market dependent upon another rework of the '38 bodies....gulp! Shades of Hudson's modus operandi (they reworked their bodies from 1936 through 1947). Now, as to what designers and approach could have prevented this slide. Their first opportunity came early in the Depression when Ray Dietrich was cut adrift from the eponymous Murray body division. His talents were picked up by Chrysler, only to be frustrated and wasted by a domineering engineering department. Although Dietrich was friends with Walter P. Chrysler, who actually hired him, WPC didn't backstop Dietrich as Sloan did for Earl. For Packard, which had benefited so greatly from Dietrich's talents, it was an oversight of tragic proportions to fail to hire him in 1932. Dietrich had, at times, contributed custom styles that may have rankled engineering but were championed by the Macauley and proved to be of considerable market merit. The artist and patron relationship was in place, needed only to be brought to bear on production designs. Attributed to Dietrich are concepts for the 120 which were very much nascent 3-box body architecture, were bypassed in favor of the safe route of the touring sedan. Less a problematic decision in '35, shortly it would become one with the '38 "shot-across-the-bow" 60 Special, to a full-fledged market crisis with the '40 GM Torpedo C-body. Another missed opportunity was failing to engage Dutch Darrin as design consultant when his '38 Eight-based customs came to grab public attention piloted by Hollywood glitterati. Macauley and company may have been worried about offending staid, conservative customers. As long as they offered a few such long-wheelbase sedans/limousine, that market was still their oyster. After all, Cadillac built the 75 for those who would consider nothing other than an over-cabbed touring sedan. Surprisingly, those conservative customers were changing their outlook to encompass more stylish progressive designs as well. One additional young designer that came to Packard's attention during the Darrin episode was Art Fitzpatrick who was responsible for the '40 Darrin Sport Sedan design. He had the potential to do for Packard what Bill Mitchell did for Cadillac. Others such as Bob Bourke, Gordon Buehrig could have been enticed to join Packard design had management resolved to make it's styling department as capable as those of it's competitors. Within, Howard Yeager and John Reinhart should have been given the freedom to design without engineering interference. The central point is that with a full-developed styling department staffed by highly-talented designers supported with the patronage of upper management rather than dominated by engineering could have made all the difference. Your thoughts sought. Pose a simple "What If", get a dissertation! Steve

Posted on: 2012/4/8 10:58

|

|||

|

||||

|

Re: 1952 Patrician - Derham or Henney?

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Home away from home

|

Hi Owen

All I have to add is conjecture for what it's worth. I can think of no cars in the postwar years of Derham's operation that they stretched the wheelbase. Their stock and trade was customizing of sheetmetal and trim, partition windows and application of padded formal tops in tan Haartz cloth. As far as how the coachbuilder created it, if one covers the image from the B-pillar rearward, it looks to use the production two door sedan front door. The rear door is unique, stretched by splicing together sections from two shells. The trunk looks to be standard length and a tad proportionally short. The 133" to 140" wheelbase range sounds reasonable. As Henney was their primary coachbuilder, I would opine that Packard channeled a customer order for this unique and highly desirable formal sedan to them. I recall seeing it offered on Ebay 5-6 years ago and dearly hope it is now in the restoration process. As it stood, it was badly rust damaged so a solid donor Patrician and additional component parts would be required to complete a restoration. Note the Phoenix Craigslist listing which demonstrates Patrician ready availability for such an effort. Hopefully someone with hard facts of the provenence will weigh in. Steve

Posted on: 2012/4/6 18:42

|

|||

|

||||

|

Re: PMCC Exec: Ed Cunningham Passed Away

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Home away from home

|

Ha-ha-ha-he-he....Phartedon White....he-he-he-he!!!!!!

Thanks Mr. Cummingham, it's a classic! Steve

Posted on: 2012/4/5 18:56

|

|||

|

||||